|

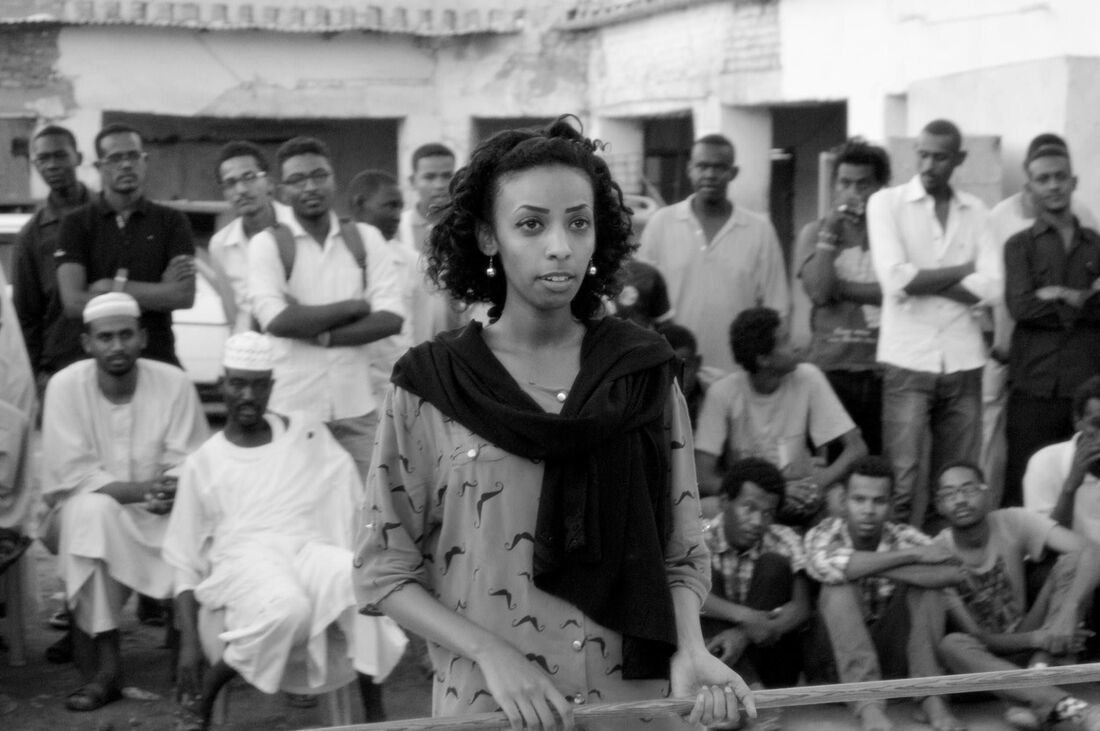

Leem Elnageib  The author, in one of Shwaryia's performances on the streets of Khartoum. Photo used courtesy of Shwaryia The author, in one of Shwaryia's performances on the streets of Khartoum. Photo used courtesy of Shwaryia Editor’s note: We publish this special post by Leem Elnageib, one of the founders of DarSudan e.V., in commemoration of the Khartoum massacre, and subsequent mass protest in June 2019, and in recognition of the long legacy of artistic resistance to the alBashir regime in Sudan. ___________ In 2011, and under the slogan: “We do not change what is on the earth, but we develop it in a way that pleases the birds and the dreams of the little ones”, a street theater initiative was launched by a very small group of young women and men in Khartoum. We were united by friendship, a love of life, a sense of humor and rejection of the big prison built by the dictatorship of Omar alBashir. This dictatorship, in place since a military coup in 1989, had turned walking the streets into a punishable crime for some. Our small group decided to rebel against the prison and the jailer both by challenging this reality in our own way. The initiative, an independent one, centered on the streets, being an experiment with a form of street theater that concerns itself with issues around the daily social and political life of the Sudanese people. The works presented by the group, sometimes accompanied by exhibitions, were in the form of short sketches that touched people’s concerns using an artistic expression that has a lot of spontaneity and beauty — a mixture of theatrical, lyrical, and poetic forms as well as drawing throughout the show.  Photo courtesy of Shwaryia Photo courtesy of Shwaryia In describing the group, Amna Shaheen, one of the founders of the group, said: “Shwaryia is an independent body that is not affiliated with any initiative, organization, institution or political party. It does not offer its work for money and does not receive money from any party. The group is not eager to change fate, but we can change reality in the simplest way. Shwaryia are young women and men who make wings of singing, poetry and acting — flying those wings in the streets of Khartoum, spreading light in the darkness of souls and hope in the hearts of the audience”. Shwaryia, the name given by us to the group, means “street people” or “people who live on the street”. The name Shwaryia embodied the idea of the street as a source of creativity and resistance, and as a vast space for freedom and human communication — the space where the spark of change lies. The negative connotation of the word was deliberately blurred by us and instead, we adopted a revolutionary conception of the word which we introduced through our street theater. From the beginning, Shwaryia was ruled by strict conditions and principles, as the group vowed it would stick together no matter what happened, that it would not turn into an elite group no matter what happened, and that it would link with the street and its pulse no matter what happened. The only conditions for joining Shwaryia were creativity in any art form and to accept practicing this creativity on the streets. As one of the group's poets, Makki Ahmed, said: "It is our right to dream and to fight as is the land, the home, and the heart is also an open street. With amazement and love…and humanity… with gathering here or gossiping there… we must find you and sing with you for freedom ...” The group gathered next to Fatuma sitt al-shai (Fatuma, "the tea lady", a tea seller) on Nile Street, a long avenue directly parallel to the Blue Nile in Khartoum. Along the side of this street sat different tea and coffee sellers, most of whom are women. People sat around sittat al-shai (“the tea-ladies”) enjoying the nice view. We gathered around them too, reviewing ideas, conducting rehearsals, and presenting the show. We were confident that we would find our audience: passersby concerned with the rising cost of a loaf of bread and the price of the bus ticket. We knew that this audience would attract a further audience until the saying proved true: that the audience comes to the theater, not the theater to the audience. Shwariya did not have a fixed audience, as it was a mobile theater that roamed the streets and markets to perform. We did not have a specific method to promote our shows; with the passage of time, we promoted them on Facebook by initiating facebook events and inviting our friends. Over time, we started developing a following on Nile Street by people who did not have the ability to follow us on Facebook. For that reason, we used to tell our friend, Fatuma, about the dates of our performances on Nile Street, and she would tell the interested people who came to her spot. What happened in fact is that the audience began searching Nile Street for Shwaryia performances. The day of the show was always crowded with spectators. For us, the members of the group, it was the children and youngsters, the daily workers — especially the street vendors, those who wash cars on Nile Street, and others — who were our most beloved audience, and a friendship developed between us and them. The audience’s interaction was an essential part of the performance; they interacted with the skits as if they were actors. When they liked a scene, they would ask us to repeat it or they presented the scene with us, and sometimes they chose their favorite skit and their favorite songs. After the initial performances, the group expanded and added to its members a number of young women and men. In total, we presented fifty-nine events in the streets of Khartoum, most of them on Nile Street. We also performed a sporadic number of shows in the markets and other gathering areas in the three cities that make up Sudan's capital, Khartoum, transforming the street into a wide theater. Of course, working in street theater in Sudan was (and remains) not without danger and risk. A number of our colleagues were arrested by the security services and interrogated for hours. They were beaten, tortured and had their hair shaved. We also had a problem with the police, even though we did not break any laws, since we did not use any loudspeakers or complicated equipment. Still, they asked us to stop our performances and leave, and sometimes they chased us or interrogated us. But the danger did not always come from the police or the security services. For example, we presented a show in a neighborhood called Al- Salama, east of Khartoum. Before the show began, the people of the area stopped it because of the presence of females in the group, which according to them, was unacceptable.

In 2014, the group’s activities decreased and receded due to the preoccupation of its members — some traveled and expatriated due to the stressful economic conditions and the responsibility they carried towards their families, and some were subjected to security persecution. There were many attempts to address the situation, but in the end, we preferred that Shwaryia become a memory — a distinguished experience that the next generation can learn from and develop in a way that aligns with their dreams and ambitions. I learned from Shwaryia something that stayed with me: that arts are one of the most important and effective tools for transferring knowledge and thus contributing to change.

0 Comments

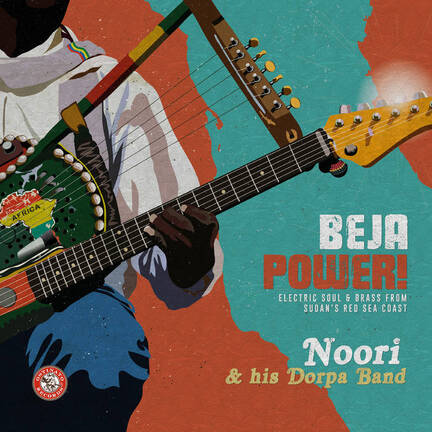

Mihera Abdel Kafi  Album cover. (c) Ostinato records Album cover. (c) Ostinato records Following the release of “Abu Obaida Hassan & His Tambour: The Shaigiya Sound of Sudan” and “Two Niles to Sing a Melody: The Violins & Synths of Sudan”, Ostinato Records is on the cusp of releasing its third Sudanese record: Beja Power! Electric Soul & Brass from Sudan’s Red Sea Coast by Noori & His Dorpa Band. The album, which was recorded in Omdurman, Sudan, will be fully released on bandcamp this week, on June 3, 2022, and elsewhere on June 24, 2022. For now, a song, Al Almal, can already be heard here. Ostinato Records announced the album as follows: “The first ever international release of the Beja sound, performed by Noori and his Dorpa Band, an unheard outfit from Port Sudan, a city on the Red Sea coast in eastern Sudan and the heart of Beja culture." It's worth noting here that though Ostinato Records, a New York City-based label, has been introducing stunning music from around the globe to an international (read: western) market, the label has a tendency to reproduce the "western gaze" in its marketing material. For example, when it writes that Noori and his Dorpa Band are "unheard" , we assume they mean unheard by non-Sudanese ears, since these musicians have been performing in Sudan for years. As an indigenous people, the Beja trace their presence on the land along the Red Sea coast back millennia. As such, Beja melodies have changed and evolved over many generations. The Beja featured quite significantly in the British colonial imagination as "noble savages". This was embodied in Rudyard Kiplings' poem "Fuzzy-Wuzzy" (1892), describing a battle between British soldiers, who entered Sudan as part of the imperial Sudan Expeditionary Force, and Beja (specifically Hadendawa) warriors. The force attempted to conquer Sudan in the late 19th century but initially failed, driven back by Sudanese Mahdist forces, including Beja Hadendawa warriors, at the battle of Suakin. One of the verses of the poem describe the Beja warriors, which the British nicknamed "Fuzzy-Wuzzy" (a racist slur used to mock Black people's hair) as "a pore benighted 'eathen but a first-class fightin' man;" Noori believes an unleashing of Beja music would form the most potent act of resistance in the Beja's quest for equity and justice.The neglect and contempt towards Beja communities continued in the post-colonial period after 1956. As such, the Beja have been active in demanding political change in Sudan for decades, confronting the way in which Sudanese governments have turned a blind eye to their calls for recognition and for access to the wealth of gold found in their soil. Noori believes an unleashing of Beja music would form the most potent act of resistance in the Beja's quest for equity and justice.

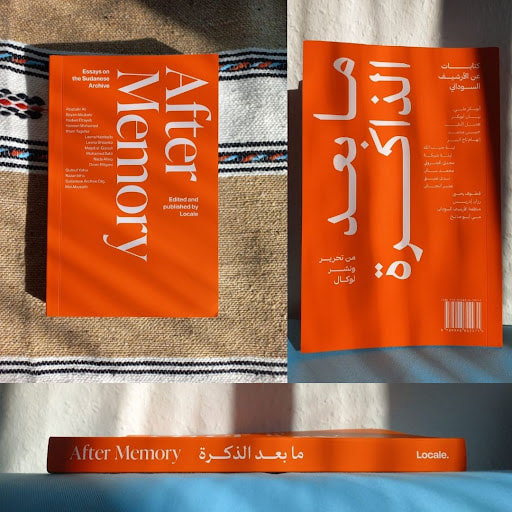

To learn more about the history of the album, but also about the amazing musicians behind it, you can read the following articles written by Noori himself for Africa Is a Country and by Ostinato’s founder, Vik Sohonie, for OkayAfrica. To listen to or purchase Beja Power! Electric Soul & Brass from Sudan’s Red Sea Coast, visit Ostinato Records’ Bandcamp Mihera Abdel Kafi"This book examines the processes and mechanics of the archive: its making, its necessity, and its function in informing the future within different practices and professions. It is not only about the different journeys that the archive takes, but the different journeys that lead us, as individuals, to the archive.”-After Memory, 2021  The Locale team, composed of Aala Sharfi, Nafisa Eltahir, Qutouf Yahia and Rund Alarabi simply never disappoints. The self-described female-led platform formed in 2016 that aims to develop and support homegrown Sudanese creative efforts, recently issued the anthology After Memory — a unique collection of essays on Sudanese history, politics, culture, art and much more. Fifteen essays, each relatively short, organized in three parts, address the topic of the Sudanese archive, which for the authors is understood "as a medium of service and future-making rather than as a vessel for nostalgia". In the first part of the collection, titled “Critique”, the essays explore, among other things, what it means to search for Sudanese history in archives in Sudan and abroad, what roles anecdotes play in the writing of history, what architecture and urban planning tell us about the archive, and who is telling these stories in the first place. This first part critically engages with what it means to be writing about a (post)colonial Sudan and a young country in which most of the population is under the age of 25, about preserving and shaping this country’s own identity, but also about female representation and visibility in this archive. The second part, “Encounter”, deals mostly with the Sudanese Revolution that started in December 2018, as captured in various photographs, pictures, videos but also preserved through music and poetry. The last part, “Construct”, is dedicated to the many things that at first glance can hardly be understood as archives. From rather more plausible things, like Sudanese cuisine, to the construction project of Sudanese Sport City (SSC), the ancient Sudanese practices of Zar, the history of Sudanese physicians’ struggles with previous and current regimes , and Khartoum’s deathscapes, one understands how all these things can map part of an overall history. The point this section of After Memory makes is that not only visible things like buildings or artworks make up the archive; rather, supposedly non-visible, non-graspable things — a real-life encounter, traditions, people’s struggles and habits — all should be archived. The remarkable thing about After Memory is not only the beautiful collection of valuable stories, but also the many images it makes available. The book is fully bilingual (English and Arabic) and has been put together exclusively by a Sudanese team. Notably, it is also cataloged in the National Library of Sudan, an act that is symbolic as well as practical, given the neglect and hostility with which public libraries in Sudan have been met during the 30 years of Omar alBashir’s brutal regime. After Memory is a product of the exhibition “This Will Have Been: Archives of the Past, Present, and Future” that Locale held in Khartoum at the end of 2019. As Locale writes: “This book examines the processes and mechanics of the archive: its making, its necessity, and its function in informing the future within different practices and professions. It is not only about the different journeys that the archive takes, but the different journeys that lead us, as individuals, to the archive.” The different articles were written by Bayan Abubakr, Magdi el-Gizouli, Leena Shibeika, Razan Idris, Hadeel Eltayeb, Haneen Mohamed, the Sudanese Archive Organization, Leena Habiballa, Mohamed Satti, Qutouf Yahia, Omer Eltigani, Abubakr Ali, Nada Atieg, Ilham Tagelsir and Mai Abusalih. After Memory can be purchased for 30$ (+shipping) directly through Locale’s linktree, where you can also listen to a playsit of music and sounds put together by Haneen. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed